It's hard to imagine a time when glass wasn't a part of everyday life, but for centuries, glassmaking techniques were a carefully guarded secret. Fathers passed the craft of glassmaking to their sons, but rarely to anyone else. Glass objects were reserved for royalty in some cultures. In others, ownership was regulated by price--if you could afford the luxury of glass, it was yours.

Glass is an artisan's dream. It can be poured into molds. It can be cut and polished into faux gemstones. It can be stretched and pulled into any shape imaginable. So, it's no wonder that creative people throughout the world choose to express their artistic talents with glass. Lampwork beads are just one form of the varied glassmaking craft.

Lampwork (or flamework as it is sometimes called) is the process of using a torch flame to melt glass rods to create shapes. The shapes don’t always have to be beads, but since that’s what I feature here, that’s what I’ll be talking about in this discussion.

In general, lampwork refers to beads made with soft glass (Moretti, Effetre, and Bullseye being some of the more popular brands). It’s more prevalent because it’s easier to work with. Most beginning lampworkers start learning with soft glass because all it requires is a simple “hot head” torch and MAPP gas from the hardware store.

Here’s an example of “soft glass” beads:

This particular set is by Krystal Kelly of Luna Beads and features white and pink glass.

The other type of glass used in beads is “hard glass.” It can also be referred to as borosilicate (boro), pyrex, Northstar, etc. It requires a specific type of torch and gas to produce a hot enough flame in order to work with this glass. Boro glass is often used in the making of shape or figure beads although soft glass can be used for this as well.

Here’s an example of “boro” glass:

To make a basic bead, lampworkers use a torch to melt the tips of glass rods. Then, they wind the molten glass around a mandrel (a narrow stainless steel rod.) The mandrel is coated with a substance called “bead release” so that the bead does not permanently stick to the rod. Later, when the bead is removed, the space occupied by the mandrel becomes the hole used to string the bead.

A lampwork artist understands the glass and the torch, knowing how much heat it takes for glass to flow, how much heat can be applied to a bead that's already shaped before it becomes molten again and loses shape, when to add decorative effects, and how different colors of glass interact with each other.

Lampworking is a skill that takes a great deal of practice. Glass cools from the outside in and the outer layers shrink as cooling takes place. Bringing a bead out of the flame and leaving it in the open air allows the outside of the bead to cool rapidly around its molten interior. A stress point develops between the cool, shrinking glass and the hot center. The stress can cause a bead to crack, either immediately or at a later time.

To prevent cracks, beads must be annealed then slowly cooled. The best way to do this is in a kiln, where temperatures can be closely regulated. The beadmaker anneals, or "soaks" the beads to make sure that all glass within them is the same temperature. The soaking temperature is high enough for glass to flow on some molecular level, but not so high that the bead ends up in a puddle on the kiln floor. After annealing, the artist begins to reduce the heat in the kiln, taking several hours to bring the beads to room temperature.

This process produces glass beads with less stress, so they're less likely to crack. Very small glass beads are sometimes slowly cooled between layers of insulation. It's not the same as annealing, but the process is usually successful because the small amount of glass in tiny beads cools at a more even rate.

Lampwork beads can feature many different decorative techniques. Beads can be as plain or as decorative as the artist likes. Dots of colors can be manipulated to form designs. They can be left as bumps on the bead’s surface or plunged into the center of the bead for a totally different look.

Fine lines are possible when craftspeople work with tiny rods of glass--kind of like painting with a glass paintbrush. This is referred to as "stringer" work and results in beautiful scroll-like designs.

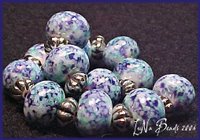

Beads can be rolled in crushed glass known as “frit” as seen in this set by Krystal Kelly of Luna Beads:

She's taken a simple white base bead and rolled it in frit (glass dust) in shades of purple and aqua.

Multiple layers of glass can be added, switching colors to create the desired effects. Other materials such as silver or gold foil or precious metal fuming can also be added. This set of beads has foil buried beneath layers of transparent green glass:

This set also shows off some of the new shapes of "pressed" beads that are quite the rage among beadmakers right now. This particular shape is called a "pillow" but there are also lentils (flat, disk shapes), lozenges, bicones and more. These shapes are created by winding glass on a mandrel as usual and then placing the round bead into a bead press to create the desired shape.

Some artists are adding cubic zirconias inside their beads for a bit of added sparkle. Here are examples of that technique from artists Lish Diffendarfer

and Kim Miles

I particularly like the way that Kim has put the CZ's into a clear bead instead of where they are typically used which is as the center of flowers. Although, don't get me wrong, she makes the most fabulous flower beads on the market, in my opinion. It's just nice to see something different for a change.

When selecting lampwork beads or jewelry featuring lampwork for purchase, here are a few things to consider:

- Are the shapes of the beads pleasing? They're handcrafted, so expect some variations—that's part of their charm, but the overall look should be attractive and the sides should fit nicely against other beads used in the piece.

- Holes should be clean and free of bead release. The lampworker should have removed the gritty bead release that was used to coat the mandrel in order to make the bead easy to remove. If the lampworker didn’t do it, then the jewelry artist should have taken care of it before designing with those beads.

- The beads should be described as “kiln annealed”, have rounded or 'puckered' ends (soft - not sharp), and have no cracks or crazes in the body of the bead.

- And sometimes all of that is not enough - I recently learned I'd been taken in by an unscrupulous ebay seller called "Austin Hamilton" who advertises "his" lampwork beads as being kiln annealed when it turns out that they are not. Nor are they made by an artist. They are mass-produced in China and are junk - and yet appear to be of decent quality when viewed in person. So BE CAREFUL! If the price seems too good to be true on lampwork - it most likely is FAKE!

All of this leads me to answer the question that is most often asked about lampwork – WHY ARE THESE BEADS SO EXPENSIVE?! I have to admit, the first time I picked up a lampwork bead at a show and looked at the price, I nearly keeled over. Thirty-five dollars for ONE bead seemed totally outrageous. Normally, I can pay less than that for an entire strand of pearls or stones. Looking back, I realize that the bead had an incredibly detailed underwater scene on it complete with kelp, fish and shells. It was easily worth the price as marked.

Let’s take a look at what’s involved in creating a bead. First, there’s the equipment. The kiln alone can be close to a thousand dollars when purchased with a pyrometer or digital controller - at least one of which is required to get the kiln to the correct temperature. Imagine buying an oven with no dials or displays and trying to figure out how to preheat it to 350 degrees to bake cookies!

Then, of course, a torch is required. Although it’s possible to start out with an inexpensive ”hot head” type of torch, most serious bead makers move on to more advanced torches such as a Minor bench burner or some other type of more expensive but better quality torch. These torches require a combination of oxygen and propane gases. Tanks of those gases as well as the equipment to safely handle and secure them are also required. Add to that the smaller equipment: mandrels, bead release, glass rods, graphite paddles and shaping tools, safety glasses, fire blankets and other fireproofing equipment.

On top of that, there’s the time commitment. It can take hours and hours to just learn to make a simple round bead with a good shape and a clean hole. Then there’s the danger factor – torches and glass get HOT, people! And, as I learned to my dismay in my first lampworking class, hot glass can cool enough to APPEAR to be cold glass, but still be hot enough to give you a nasty, nasty burn. Now, add in all the minute details of stringer work, frit, or making a shaped bead (animals, vessels, etc.) and you’re talking a major time investment...and labor MUST be figured into the price of the finished piece.

I’ve found it helps if you think of these pieces not as beads in the traditional sense, but as small works of art. They’re really miniature paintings or sculptures in glass and each one is unique and individual. They should be priced accordingly.

Still, it’s possible to get decent deals on lampwork if one shops around wisely. I try to get beads of the highest quality I can afford for use in Silver Parrot Designs jewelry. I never purchase beads unless they are certified to be kiln annealed and I only do business with glass artists who have proven track records of providing good quality work.

While I try to keep the prices as reasonable as possible, occasionally, I’ll dig deep into my pockets for some work I find truly outstanding and that price will be reflected in the finished jewelry piece. And, frankly, there are a few artists who’ve priced themselves right out of my range. While I think they are absolutely entitled to charge what the market will bear and get every penny they can for their work, I simply can’t pay that amount for focal beads, then add on the additional materials, labor cost and profit to make a piece of jewelry out of them and expect my customers to be able to afford the end result.

Thus endeth today’s lesson. I’m hoping to get some jewelry-making time in this weekend to use some of the great beads I’ve featured today and in earlier posts. It’s supposed to be rainy and cold (finally some winter weather!) so it’ll be perfect for staying and playing IF I manage to get all the chores done first.

Dang it - who invented chores anyway? Probably a man, I'll bet ;-)

KJ

No comments:

Post a Comment